By funkhaus

In the fall of 2022, the Cornell Journal of Architecture released their twelfth issue titled “Looking at After”, which analyzes the longevity of architectural works in an ever changing environmental and social landscape through contributions from architecture faculty, students, alumni, and visitors. The feature of Studio Luz Architects’ work and perspectives in this journal, penned by principal Architects Hansy Better Barraza and Anthony Piermarini, is a dialogue on responsibility in dismantling anti-Black design curricula and spaces. The publication showcases a handful of prominent projects along with how these structures grapple with their ability to deliver equity and opportunity for communities of color in the studio’s home city of Boston and the New England region at large.

As the Coronavirus Pandemic delayed publication of this journal, it all came to affect its contents as contributors were forced to examine the effects of the pandemic and its subsequent social inequalities and movements on their work. Close examination of these issues has been a core element of Studio Luz’s work since its inception. In their essay “Work To Do”, Anthony and Hansy engage in conversation with one another to uncover subconscious bias, connect their work to their personal values, and bring forth a vision for the future of the studio and their profession as a whole. “We are in a moment of significant historical change. At the moment, the pandemic is raging, and we are actively participating in the BLM movement here in the USA” began Anthony, opening up the conversation. “The idea for this dialogue occurred after observing that the responsibility and appeals to respond to the institutional racial inequities and discrimination experienced by Black students in the academy disproportionately fell on one of us, who identifies as a person of color.”

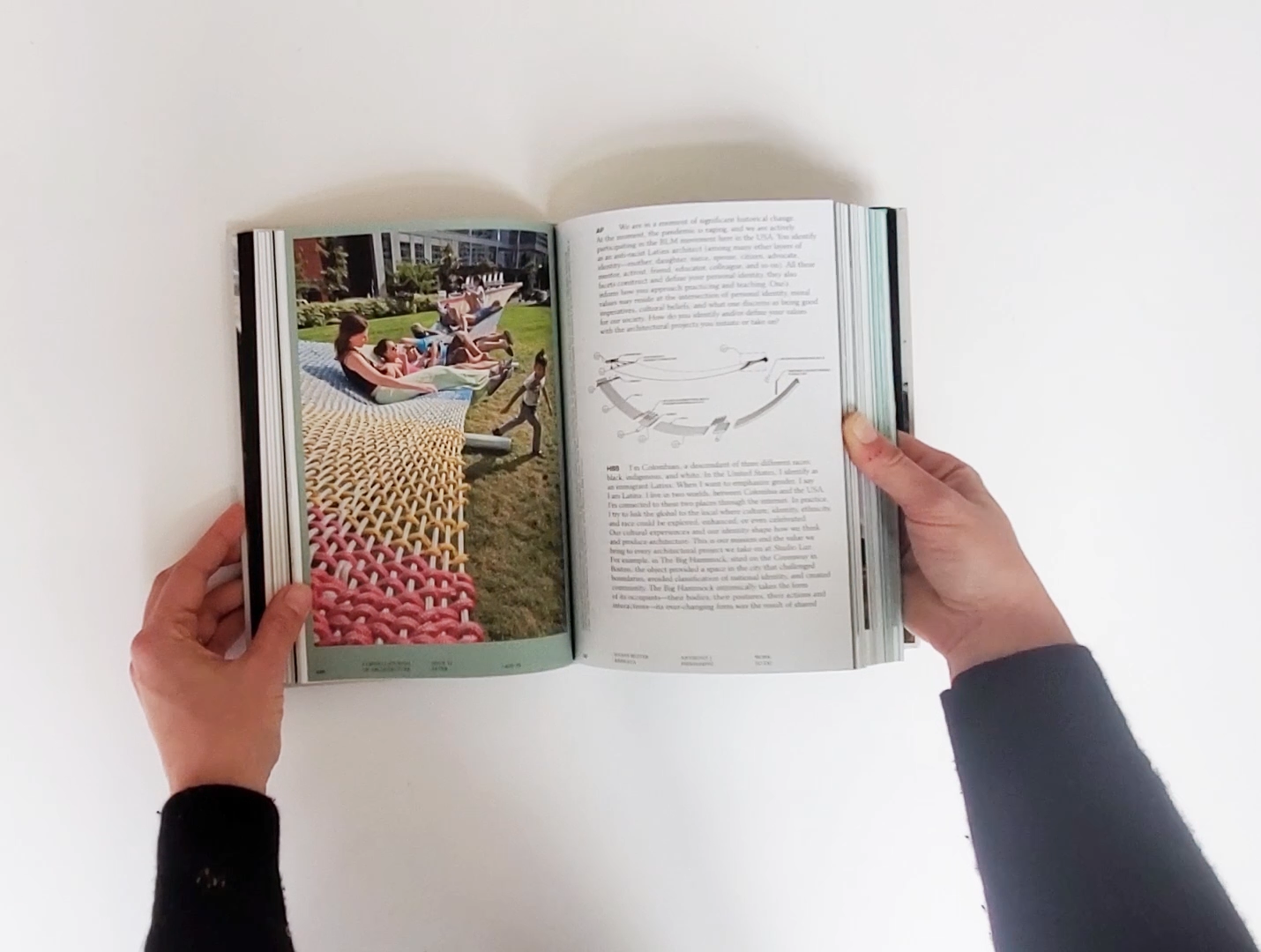

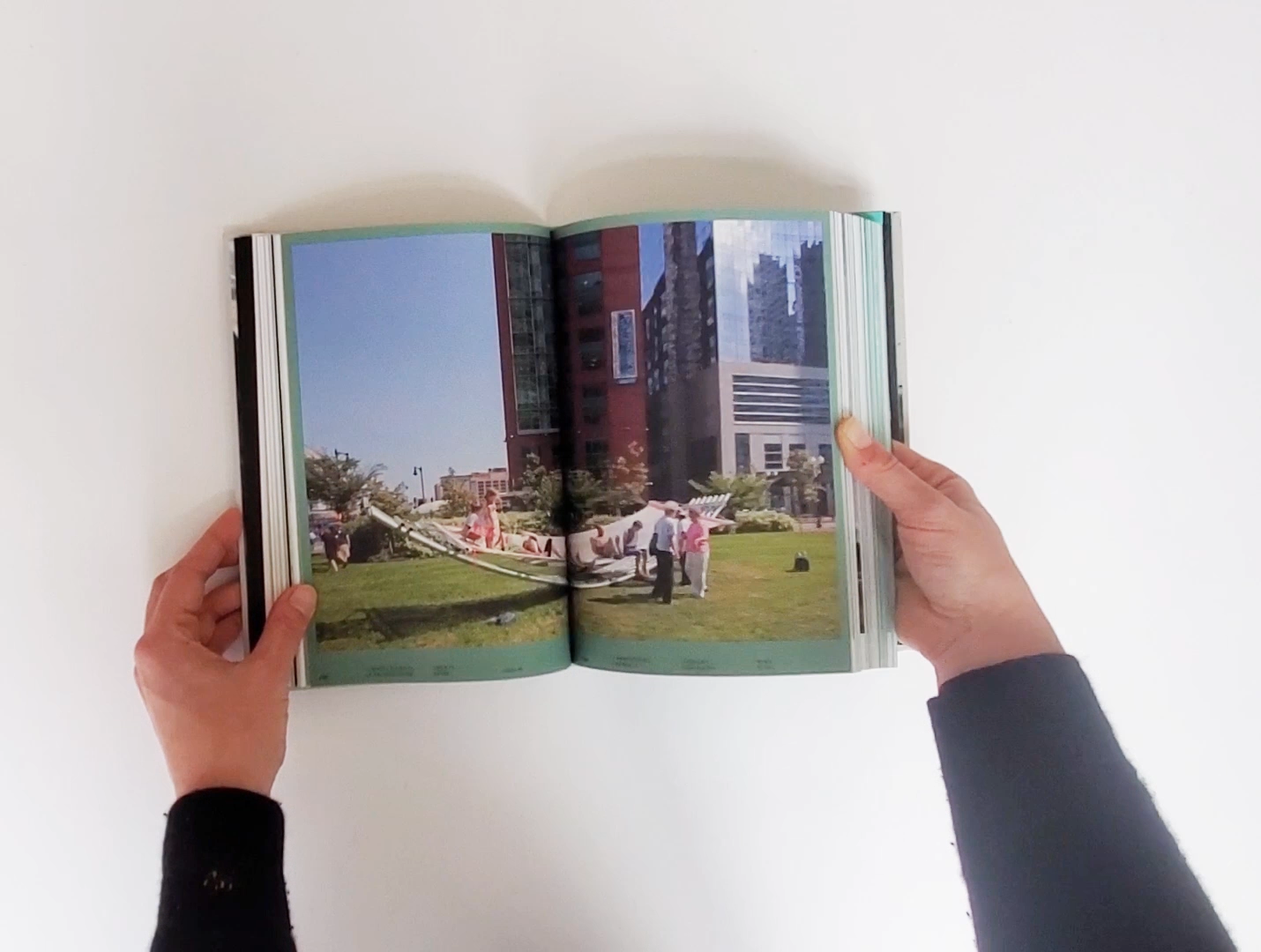

“I’m Colombian, a descendant of three different races: Black, Indigenous, and White. In the United States, I identify as an immigrant Latinx.” Hansy responded, leading into an examination of her identity and how it ties to the public installation project “The Big Hammock” sited on the Greenway in Boston. “The object [The Big Hammock] provided a space in the city that challenged boundaries, avoided classification of national identity, and created community. The Big Hammock intrinsically takes the form of its occupants—their bodies, their postures, their actions and interactions—its ever-changing form was the result of shared experiences.” Hansy then goes on to discuss the way the hammock is interpreted by different viewers and users. The woven structure of the hammock, made from recycled milk bottles, includes multiple colors which were selected to imbue the surface with multiple associations, such that people with various cultural heritages may relate to the woven surface differently initially, and engage in a shared experience that leads to connection and understanding.

Raising important questions in regards to their work with the Wellesley College Acorn House, a center for Asian, Latina, and LGBTQ students and advising faculty, Anthony Piermarini notes that he aims to eliminate his personal “blind spots” by allowing for other voices to be heard – particularly in the classroom where he nurtures the next generation of architects. Anthony and Hansy are both educators, looking towards curricular changes which move academia towards equity. “I strive to create learning experiences for students that reflect their own values, sense of personal identity, and discuss how their specific viewpoints inform decision making” writes Anthony. “As a White male, I recognize my privileged position; I am very conscious of the words and images used in the way I teach. To even begin to undo white supremacy, we must acknowledge that it exists and that racism is informing architecture today.” The Wellesley College Acorn House stands as a unique example of work which emerges from the political will of an institution rather than the commodity of architectural production for capital gain.

When approaching the work there is to do in the field of architecture to create more sustainable and just cities, Studio Luz is always doing what the title of this publication suggests – looking at after. In keeping a future-focused mindset, Hansy and Anthony have deeply rooted their values into their work and envision new dynamics between clients, user groups, and the built space. “I will continue to advocate for design commissions that go directly to support BIPOC-led firms” concludes Hansy. “This is key to the survival and longevity of these firms in the re-imagination of the equitable city we long for.”

Click this link to view the full section of work contributed by Hansy Better Barraza and Anthony Piermarini to Issue 12 of the Cornell Journal.