By funkhaus

Once a 1920’s film warehouse, 69 Church Street in the Historical Bay Village Neighborhood is now the site of 6 mixed-use residential units, though its original charm remains. Anthony Piermarini, Principal in Charge, AIA, CPHD worked with developers J.B.Ventures and TCR Development and led the SLA team in creating a design that transforms Church Street, preserving the historic beauty of the building while incorporating a new modern addition that extends from the façades to the interiors. We spoke with Anthony about his experience working on the Church Street project and how they were able to honor the original design of the building while making improvements that best serve the community.

Tell us about the restoration of the facade. Why was it important to restore and preserve, and what steps did you take to do so?

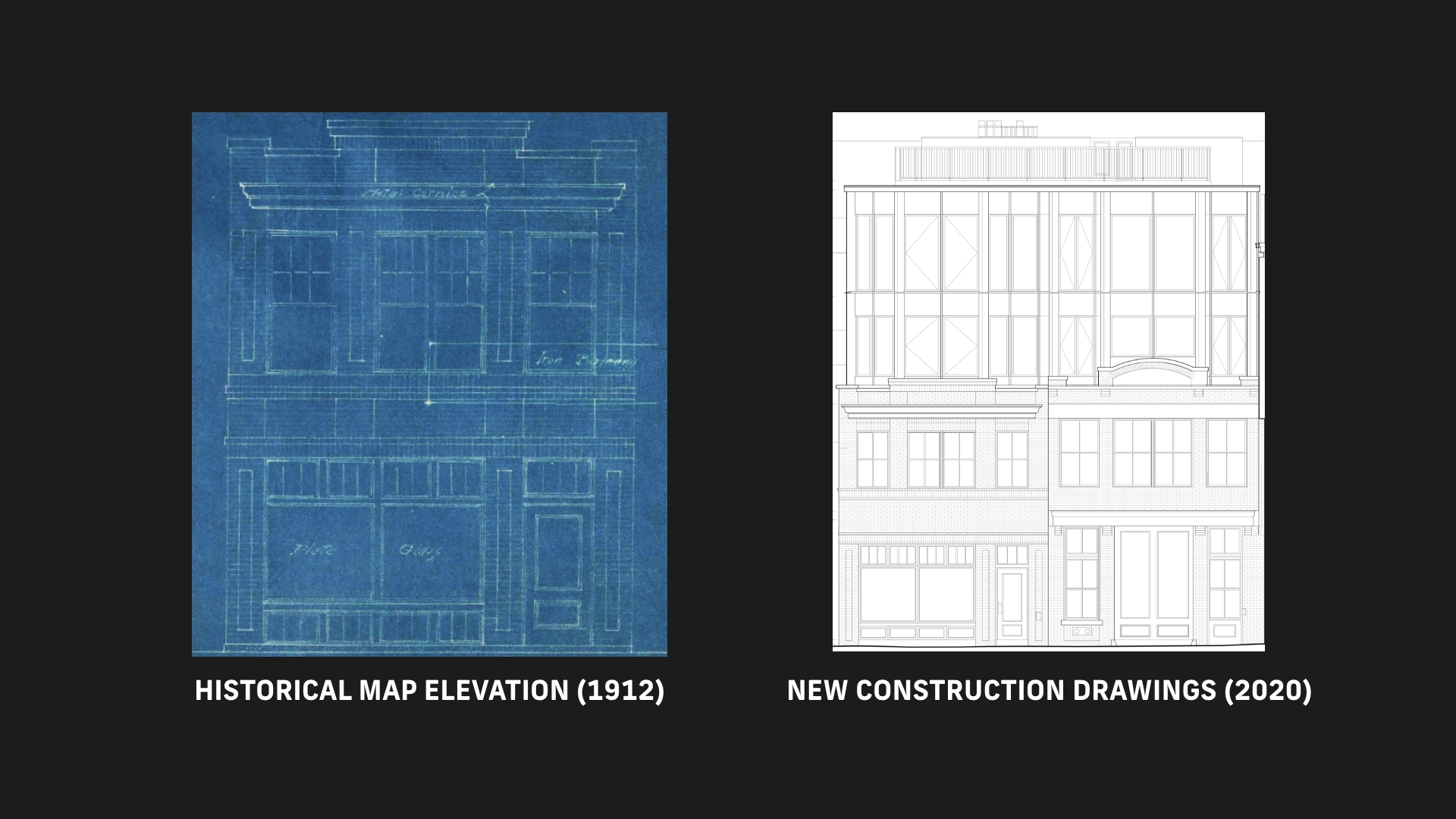

The Church Street building is in a historic landmark district, so part of the agreement with the neighborhood was that it be restored at the ground level, as close to the original conditions as possible. That process required removing many years of renovations to the building and then reconstructing its original facades. As we went through historical documentation, we found various alterations had been made over time, so we had to make some reasonable interpretations as to what was appropriate in terms of restoring it to original conditions. We met closely with preservationists and with the city to review what was feasible given the current building code and intended use.

What were some of the structural challenges you faced during the restoration process?

From a technical standpoint, it was incredibly challenging — when you’re working with historical buildings, especially when you try to build within them, you’ll discover that the structure is not up to the current codes. The Church Street structure was actually two buildings, side by side with a shared wall in the middle. One building was a combination of load-bearing masonry, all brick on the outside with steel and concrete floors on the inside, and the other one was a combination of load-bearing masonry with a concrete frame inside. That was an interesting puzzle to solve from a structural standpoint, as none of the existing structure could be reused to support anything new. We ultimately braced the building shell and put an entirely new steel frame behind that, one that met all the current seismic conditions. The new steel frame behind the existing facades was clipped on and held the outside of the building together, and from there we were able to build upwards. Our structural engineer, who has been working over about 30 years in Boston, said it was one of the most complicated restoration projects he’s ever worked on. There was definitely an engineering feat that happened there, which was done in close collaboration with our geotechnical engineers, The Geotechnical Consultants, and our structural engineers, Roome & Guarracino.

What were some of the aesthetic challenges you faced during the restoration process?

It was key that we stayed true to the character of the building for the restoration by finding materials that would match the existing materials as closely as possible. We had existing bricks between the two buildings that didn’t match each other, so we had to search for materials that would make them uniform, and that seamlessly integrated the new addition into the existing structure. We wanted to use materials that had a timelessness to them, so we selected bronze-toned panels that are classic but contemporary at the same time.The search for materials paid off, and the new addition to the building is complementary to the original design. We call it woven — not in the sense that it’s woven out of fabric, but that it takes the proportions and compositional aspects of the masonry base building and elevates and reflects them in a new way. We hope that the addition will stand the same test of time and continue to contribute to the character of the neighborhood positively for another 100 years.

What resources did you use to gather information about the history of the building?

We used archival resources through the Boston Public Library throughout this project. They are an incredible resource, and they were a key research partner in this — shout out to the public library system here in Boston! With their help, we were able to find photographs, partial original blueprints, historical news articles, and other materials that would help guide us and create a conversation with the Historic Landmarks Commission, the city officials that oversaw the design for the project. That organization is composed of a mix of full-time employees of the city, volunteers from the neighborhood, historians, designers, architects, preservationists, and community advocates — they’re the group that’s helped us to determine the right level of restoration that meets the developer’s criteria for making this marketable, but at the same time really improves the public realm and keeps that character of the neighborhood.

What is the benefit to communities of architecture firms taking the time to do this kind of restoration?

Over the years, there were many poorly thought out modifications that had been made to the building, and the entire first floor of the building on the exterior had been damaged. By the time we began this project, it didn’t resemble its original historical condition in any way. This building is really important to the community there in Boston’s Historic Bay Village, which is the smallest historic neighborhood in the city. This is the building that welcomes you from Park Plaza — it’s the gateway into the district. Because of this, maintaining the historic character at the ground level was super important to everyone involved, and restoring and repairing this important building ultimately improved the public realm.

How did sustainability factor into this project?

They say the most sustainable building is an existing building. That’s because the embodied energy is already there, and with the improvement of the building envelope, it’s possible to make the building more energy efficient compared to another existing building with a leaky shell. Energy efficiency is something we need to pay attention to with all existing buildings, given that 30% of our carbon emissions come from the building sector, and 80% of the buildings that exist are not energy efficient. We’re glad that we were able to make the Church Street project not only beautiful and functional, but energy efficient as well.

Images by Jane Messinger.